Commodore PET Hardware Review

The following is a review of the original Commordore PET

microcomputer. It appeared in the Jul-Aug 1978 issue of Creative Computing. The

magazine is no longer published so the address in the following notice is

invalid but I'm including the notice per the instructions in the magazine on

re-printing their articles:

Copyright © 1978 Creative

Computing

51 Dumont Place, Morristown, NJ 07960

A Creative Computing Equipment

Profile...

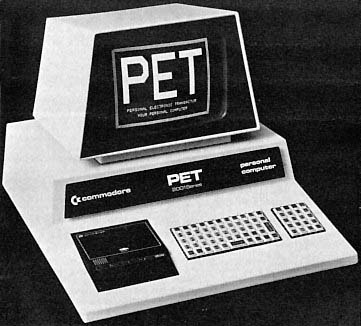

COMMODORE PET

Ludwig Braun

Commodore has been delivering their PET computer to customers

since about September, 1977. For $595 you get a computer with 4K of RAM for

user space plus 14K of ROM loaded with BASIC and an operating system. The

machine is complete with a keyboard, a cassette recorder, and a nine-inch video

monitor. If you pay $795, you get the same machine with 8K of user RAM. All of

these are built into a single cabinet, so there are no cables to connect. This

means that all you have to do to get the machine up is plug it in and turn it

on. BASIC executes in ROM, so you don't use any of your RAM for BASIC, and

BASIC is there ready to use immediately. You do lose 1,024 bytes of RAM for

scratch pad, the stack. input buffers, etc., but the rest is available for user

program, variable, and array space.

On balance, the PET is the best machine I've ever seen for the

teacher and the student. (This doesn't mean it's perfect, as I will point out.)

I feel this way because it is inexpensive. portable (I carry mine all over the

U.S, to meetings and demonstrations), reliable, and easy to use. It also has an

excellent BASIC.

Commodore's PET is one of free very few personal computers

that combines all four basic units (keyboard. computer, cassette drive, video

output) in a single package.

BASIC

The BASIC is similar to MITS 8800 BASIC. It has strings (LEFT$,

RIGHT$. MID$), graphics. and cursor controlled editing. In addition, PET BASIC

permits integer as well as floating-point representation of numbers and has

ten-digit internal accuracy. It also has a better variable naming convention

than most BASICS. It is possible to define a variable named ACTIVITY, which the

machine will accept and recognize. This means that BASIC program variables in

PET can have more mnemonic significance than is possible in most BASICS.

Actually, the interpreter recognizes only the first two characters of the name,

even though it stores the entire name in the program. If, for example. the user

enters the program

10 ACTIVITY = 5

20 ACE = 0

30 PRINT ACTIVITY, ACE

When the program is RUN. it will print

0 0

that is, both variables are treated as the variable AC, which is

set to 0 by line 20.

If the user asks for a LIST, however, the program will be listed

exactly as it appears above. This is useful in commenting within a program and

should eliminate the REM statements we have had to use in documenting programs

in the past.

Although the program line may be 80 characters long, the screen

displays only 40 characters on a line (with 25 lines displayed). Longer lines

overflow to the next line. This is a serious deficiency in the PET. For

plotting graphs, or even for text. 64 or 80 characters is far better.

Graphics

The graphics capability is impressive in a machine at this price.

There are 64 graphic characters in addition to the normal letters, numbers, and

punctuation. Each printable character may be displayed direct (white on black)

or reverse (black on white), essentially giving us 128 graphic symbols. These

graphic symbols range from thin lines through rectangles, segments of circles,

intersecting lines, and bars to the spade, diamond, heart, and club of playing

cards. These symbols may be seen in the upper-case positions on the keys in the

figure.

The PET may be put into a special mode in which the graphic

symbols over the alphabetic characters are replaced by the lower-case

alphabetic characters.

Cursor Control

The cursor control is an excellent feature for two reasons. The

cursor may be moved up, down. right, or left by hitting the cursor controls.

This permits powerful program editing. After a line has been entered, you can

change an E to an R merely by moving the cursor to the E, hitting the R, and

then hitting Return. The modification is made on the screen and in the stored

version of the program. Using the cursor controls plus an Insert and Delete

key, you can insert or delete words anywhere in a line after it has been

entered; for example. if you inadvertently enter

50 IF X=10 260

(you forgot the THEN), you can place the cursor on the 2 of 260,

insert four spaces, and then enter THEN. After Return, the line is changed.

This editing capability means that long lines don't have to be re-typed. The

second reason for excitement about cursor control is that the cursor controls

may be imbedded in a program. This essentially gives us a two-dimensional TAB

function, which together with the graphic symbols permits the display of

complex visuals. And because you can blank the screen under program control,

you can generate simple computer animations. Not only can we make programs more

interesting for the user with graphics, but we can challenge kids to create

their own graphics without requiring any knowledge of mathematics (see, for

example, the DRAW program published in the November-December 1977 issue of

People's Computers).

Cassette Recorder

The built-in cassette recorder permits the user to save programs

merely by typing SAVE "NAME" where NAME is a real name (not A. B, or Q as in

some micros). Re-entering requires only typing LOAD "NAME." The PET also has a

VERIFY command which checks to see that the cassette version is identical to

the one in memory. If it isn't, the screen displays a verify error. This

feature is very valuable and is unavailable on most micros.

The user may customize BASIC because PET BASIC has a USR function

to permit entry of user-defined machine-language routines.

Interfacing

The PET can be interfaced to the real world through any one of

four external ports which are accessible through BASIC commands. There is an

IEEE 488 interface, an eight-bit parallel port, a port for a second cassette

recorder, and a port that brings out the system bus (it's not an S-100 bus).

The second cassette recorder permits the user to put together a file management

system, although the manual makes the user nervous about making a mistake and

wiping out entire files.

Keyboard

The keyboard is, perhaps, the machine's most vulnerable component.

It looks more like it belongs on a calculator than on a computer. The

key-to-key spacing is only two thirds that of a conventional keyboard. which

means that touch typing is difficult and even a two-finger duffer like me hits

the wrong key now and then. On the plus side, the keyboard includes a number

pad and all the common symbols (+, -, *, parentheses, quote mark, etc.) are

available without requiring a shift.

Since each of the 64 graphics characters can be displayed

in white on black or black on white, 128 graphic symbols are available,

including the four playing-card symbols.

6502 Microprocessor

Commodore uses the MOS Technology 6502 (made by one of their

subsidiaries), which has a very awkward instruction set. This means that the

USR(X) function is more difficult to use than is true for most eight-bit

microprocessors. This difficulty is obvious only with the USR function. In

program execution. the PET is at least as fast as any other microcomputers

which I have tried.

Deficiencies

The PET is a great machine, but it has some deficiencies in

addition to the short screen line (40 characters) and the small keyboard. Some

of these could have been overcome at almost no additional production cost but

were overlooked by Commodore. Among these deficiencies are:

- There is no composite-video signal available to the user. This

means that a teacher who wants to use the computer in his/her classroom cannot

display the screen on a monitor. Marc Hertzberg in our lab at Stony Brook has

designed a system modification which provides this signal and which costs about

$3 worth of parts and may be installed in less than half an hour.

- There is no handle on the PET. I put on a $1 hardware-store

handle and take my PET everywhere. Actually, none of the microcomputer

manufacturers has put on a handle. Incidentally. the PET weighs 44 pounds,

which is a bit heavy. Twenty pounds is a good weight goal.

- We have a small number (three or four) of system crashes a

month on each of our three PETS. We haven't been able to pinpoint the cause but

suspect that line spikes are getting through the power supply. Fortunately.

because BASIC is in ROM, we can recover by turning the machine off and then on

again. Of course, in the process we lose whatever was in RAM. It would be nice

to have a system restart mechanism which doesn't zero the memory.

- The cassette recorder doesn't have a counter, which is a real

nuisance. If you have several programs on one tape, it is impossible to

fast-forward to a point near the beginning of the program before loading. This

means that you must start at the beginning of the tape and let it run at

regular speed until it finds and loads your program.

- The advertised transfer rate on the cassette recorder is 1000

baud. The effective transfer rate is closer to 250 baud because of overhead in

the file format (leader space, redundancy, etc.). This, combined with (4)

above, means that you must put only a small number of programs on a cassette or

wait perhaps several minutes to get a program loaded. Arthur Leuhrmann of the

Lawrence Hall of Science has solved this problem by using C5 cassettes and

recording only one program per cassette.

- Probably the most inexcusable deficiency in the PET is the sad

state of the user's manual. When we got our first PET in October, we got a

small booklet which told us how to turn the PET on, how to save and load

programs, and which merely listed all the BASIC commands. Our second and

third PETs arrived in December with a slightly larger booklet. This one gave

brief illustrations of most of the commands and a little trouble-shooting

information but still was inadequate.-In January, we got about 50 loose-leaf

pages describing the BASIC commands in adequate detail. With patience, I

suppose that we eventually will get a real manual.

- Another possible problem with the PET, at least for school

administrators, is a lack of approval by Underwriters Laboratories. This

doesn't mean that the machine is unsafe, but it is a base which Commodore

should touch as soon as possible.

- Additional memory is expensive. At a time when good 16K RAM

boards sell for less than $400, charging $200 for 4K of RAM is hard to take.

Additional RAM, beyond 8K, must be placed outside the main cabinet, which is a

bit of a nuisance. This extra RAM isn't available yet, and no costs have been

quoted.

- The fact that the PET bus is not S-100 means that all the

great boards (speech, music, Dazzler, A/D, etc.) cannot be used on the PET, All

is not lost, however. At least two companies already offer S-100 adapters for

the PET.

Conclusion

I don't want to quit on a downbeat. The bottom-line question is:

Would I buy another PET? The answer is an enthusiastic "Yes!" It is the best

classroom computer around on a price/performance basis and probably will be the

standard of comparison for other personal computers we can expect to be

introduced during the next couple of years. (Are you listening, TI?)

[Ed. note: As of the end of April, the 4K PET is not in

production, although it may possibly resume in July. Another model of the PET,

featuring a standard typewriter keyboard, is scheduled to go into production at

the end of this year; it will not include a cassette drive. and some of the

graphics functions will be dropped. A separate typewriter keyboard is also

planned for later this year, for connecting to the present PET through its IEEE

488 interface.]

|